CALL FOR PAPERS FOR OUR AUTUMN SYMPOSIUM IN THE BERLIN PSYCHOANALYTICAL INSTITUTE, KARL-ABRAHAM-INSTITUT (BPI),

BERLIN, OCT. 1st-3rd 2021

Körnerstraße 11, 10785 Berlin-Mitte

PRESENTATIONS INCLUDE:

ANGELIKA EBRECHT-LAERMANN -The destructiveness of art and beauty. Superego perversions in dreams about fascist imaginaries (Prof. Dr. phil., Training analyst, Berlin Psychoanalytical Institute, DPV)

SUZANNE KAPLAN – Letters from Bloomy (film screening and dialogue) (Training and child analyst, Swedish Psychoanalytical Association, Dr of Education Stockholm Un., Researcher, Hugo Valentin Centre/ Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Uppsala.)

JONATHAN SKLAR – Apocalyptic life and the missing debate (Training analyst, British Psychoanalytic Society)

CLAUDIA THUßBAS – Mothers made of steel – steeled babies: National socialist fantasies about motherhood (Dr. phil., Training analyst, Berlin Psychoanalytical Institute, DPV)

SZYMON WRÓBEL – Fascism as a symptom, function and ideological scheme (Professor, In.of Philosophy and Sociology, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw)

CALL FOR PAPERS:

“The premier demand upon all education is that Auschwitz not happen again”, wrote Theodor W. Adorno. He credited Freud with the profound insight that “civilization itself produces anti-civilization and increasingly reinforces it”, and added that “his writings Civilization and its Discontents and Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego deserve the widest possible diffusion, especially in connection with Auschwitz.” It is 100 years since the latter work was published, in 1921. The First World War had ended in the autumn of 1918, and the Treaty of Versailles followed in 1919. In Germany, Hitler was beginning to make use of his Storm Troopers, the SA, and in Italy, Mussolini set up the Fighting League that gave their name to fascism, the Fasci di Combattimento, and launched the fascist party in 1921.

The year before, in 1920, Freud had published Beyond the Pleasure Principle, where he introduced the death and destruction drive and discussed the compulsion to repeat. In Totem and Taboo (1913) Freud had spoken of emotional ambivalence and on the primal horde, which he continued to make use of in his further thinking of groups. “If the individuals in the group are combined into a unity, there must surely be something to unite them,” he wrote in Group Psychology, where he introduced the concepts of identification and the ego ideal. “It is not an overstatement, wrote Adorno, if we say that Freud, though he was hardly interested in the political phase of the problem, clearly foresaw the rise and nature of fascist mass movements in purely psychological categories. If it is true that the analyst’s unconscious perceives the unconscious of the patient, one may also presume that his theoretical intuitions are capable of anticipating tendencies still latent on a rational level but manifesting themselves on a deeper one.” He suggested that the aim of fascism and fascist propaganda is the opposite of psychoanalysis or the psychoanalytic process, “through the perpetuation of dependence instead of the realization of potential freedom, through expropriation of the unconscious by social control instead of making the subjects conscious of their unconscious.”

The Italian term fascismo is derived from fascio, meaning ‘bundle of sticks’, from the Latin word fasces. The name was given to political organizations in Italy known as fasci, similar to guilds or syndicates. The Fascists came to associate the term with the ancient Roman fasces, a bundle of rods tied around an axe, an ancient Roman symbol of the authority of the civic magistrate which could be used for corporal and capital punishment. The symbolism of the fasces suggested strength through unity: a single rod is easily broken, while the bundle is difficult to break.

While there is no one agreed-upon definition of fascism, the historian Stanley G. Payne focuses on three concepts: 1. The “fascist negations”: anti-liberalism, anti-communism, and anti-conservatism; 2. “Fascist goals”: the creation of a nationalist dictatorship to regulate economic structure and to transform social relations within a modern, self-determined culture, and the expansion of the nation into an empire; and 3. “Fascist style”: a political aesthetic of romantic symbolism, mass mobilization, a positive view of violence, and promotion of masculinity, youth, and charismatic authoritarian leadership. Robert Paxton defines fascism as: “a form of political behaviour marked by obsessive preoccupation with community decline, humiliation, or victimhood and by compensatory cults of unity, energy, and purity, in which a mass-based party of committed nationalist militants, working in uneasy but effective collaboration with traditional elites, abandons democratic liberties and pursues with redemptive violence and without ethical or legal restraints goals of internal cleansing and external expansion.” Fascism tends to be racist, and most scholars place fascism on the far right of the political spectrum, focusing on its social conservatism and its authoritarian means of opposing egalitarianism.

To Jason Stanley, the most telling symptom of fascist politics is division, its aim of separating a population into an “us” and a “them”: “As the fear of “them” grows, “we” come to represent everything virtuous. “We” live in the rural heartland, where the pure values and traditions of the nation still miraculously exist despite the threat of cosmopolitanism from the nation’s cities, alongside the hordes of minorities who live there, emboldened by liberal tolerance.” With reference to the extreme right Jobbik party’s election posters, Ferenc Erós described how one of them read: “Budapest is the capital of the Hungarians”. “At first it seems to be a completely harmless declaration […] However, there is a simple rhetoric trick in it: instead of saying that “Budapest is the capital of Hungary, which is an obvious geographical and administrative fact, the statement on the poster presupposes that if Budapest is the capital of the Hungarians, it cannot be the capital of other peoples. The sentence implies the exclusion of others, the non-ethnic Hungarian citizens, such as Romani and Jews, who are, by the force of this definition, “foreign occupants”. This aim of drawing a distinction between a “real people” and its opposite, exemplifies the fascist belief in hierarches of power and dominance, grounded in nature, that are inconsistent with equality of respect between people.

Within the fascist mindset, the leader is analogous to the patriarchal father, the head of the traditional family. If the fascist demagogue is the father of the nation, any threat to patriarchal manhood and the traditional family undermines the fascist vision of strength. These perceived threats include the crimes of rape and assault, as well as sexual variety, viewed as deviance. Fascist propaganda promotes fear of interbreeding and race mixing, and the “enemy” is often portrayed in highly sexualised ways. “In the history of the United States, the fraudulent rape charge stands out as one of the most formidable artifices invented by racism”, wrote Angela Davis. “The myth of the Black rapist has been methodically conjured up whenever recurrent waves of violence and terror against the Black community have required convincing justification.” In Klaus Theweleit’s account of the fantasies of the men of the Friekorps, a forerunner to the SA, it becomes clear how their hatred and dread of women, rather than linked with Oedipal triangulation, arises in the pre-Oedipal struggle of the fledgling self; a dread of dissolution, of being swallowed, engulfed, annihilated. In these men’s imaginations, women are either indistinct, nameless, disembodied or vividly, aggressively sexual and threatening. Within universities, fascist thinking denounce disciplines that teach perspectives other than the dominant ones, and its opposition to gender studies in particular flows from its patriarchal ideology. As a field that promotes gender equality and problematises relations between genders and sexualities, gender studies has come under official attack in Russia, Poland and Hungary, and has been under fire from far-right nationalist movements across the world.

Contemporary conflicts around calls to decolonize the curriculum may also be seen in this light. The Rhodes Must Fall campaign aims to address racial abuse and injustice, as well as addressing curricula that represented culture and civilization as the product solely of white men. Hannah Arendt describes how imperialism combined racism and bureaucracy in “administrative massacres” which foreshadowed genocide on European soil. The violence Europeans perpetrated towards people on other continents was later brought back to Europe: “Imperialist rule, except for the purpose of name-calling, seems half-forgotten, and the chief reason why this is deplorable is that its relevance for contemporary events has become rather obvious in recent years.” Simukai Chigudu, associate professor of African history and politics at Oxford, writes of the colonial legacy and the shadow of Cecil Rhodes: “Saints’s rituals of dominance and sadism were only some of the ways that it taught its boys to accept the logic of colonialism. Wasn’t it only natural that older students ought to wield power over younger ones, or that those who excelled at sports or schoolwork be granted privileges, like the ability to tread on certain college lawns, that were denied to lesser children? Wasn’t it right that those who stepped out of line be forced to labour, or even whipped? These were perfect lessons for a world in which one race thought itself worthy of violently subjugating another.” He continues: “Unlike many of our critics, we at least recognised that the statue of Rhodes did not actually exist in the past. It is not a sterile historical relic, or some accurate record of prior events. It is a piece of self-conscious propaganda designed to present an ennobled image of Rhodes for as long as it stands. […] If anyone was trying to erase the past – specifically the history of subjugation and suffering on which his fortune was built – it was Rhodes. I had to wonder why many eminent white commentators were so attached to him.”

These reflections relate to the theme of how historical events are remembered and commemorated. In Arendt’s words, “all historiography is necessarily salvation and frequently justification”, thus how do you write historically about something you do not want to conserve, but on the contrary, feel engaged to destroy? And how are some memories socially organized so as to cover over other memories? In the histories of anti-fascist resistance, the slogan ¡No pasarán! (They shall not pass!) was taken over from the Spanish Civil War, ultimately lost by the Republican troops, to the Battle of Cable Street, London, where the local East End Jews, Irish, socialists and communists won against the police and Oswald Mosley’s supporters. We may also pose questions over conflicts over how to imagine anti-fascist resistance, contemporary as well as historically.

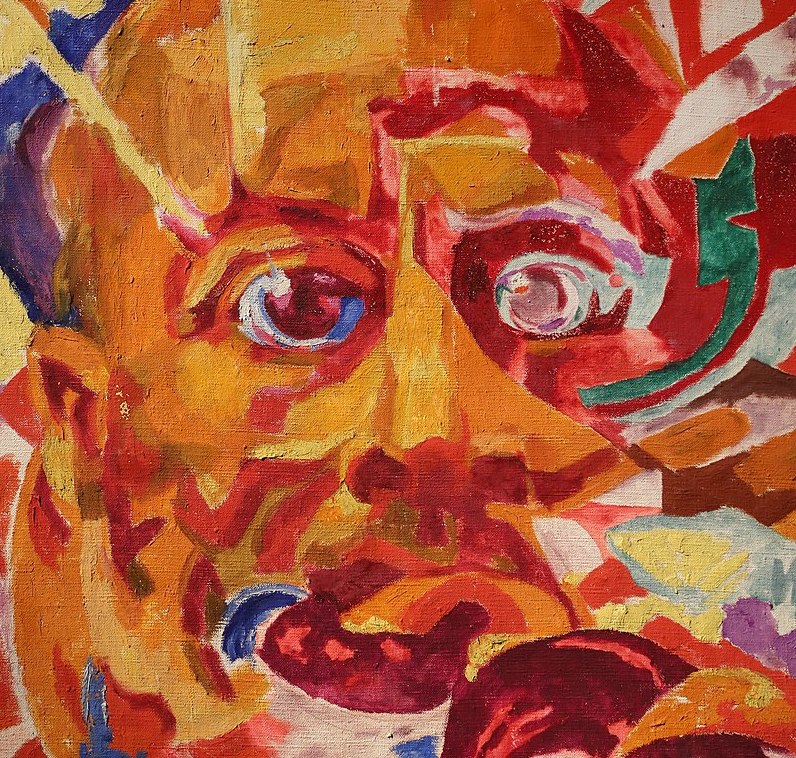

“Since it would be impossible for fascism to win the masses through rational arguments,” wrote Adorno, “its propaganda must necessarily be deflected from discursive thinking; it must be oriented psychologically, and has to mobilize irrational, unconscious, regressive processes.” In line with this reasoning, this conference is concerned with fascist images, the fascist imagination, how this ideology appeals to and aims to stir up affects and fantasies, conscious and unconscious, about self and others, pasts and futures, bodies, boundaries, threats and desires, hardness and fluidity. We encourage contributions that consider fascism and fascist movements and tendencies from different geographical perspectives and locations, and that engage with different aspects of this theme, not just in the past, but in our present.

***

This is an interdisciplinary conference – we invite theoretical contributions and historical, literary or clinical case studies on these and related themes from philosophers, sociologists, psychoanalysts, psychotherapists, group analysts, literary theorists, historians, anthropologists, and others. Perspectives from different psychoanalytic schools will be most welcome. We promote discussion among the presenters and participants, for the symposium series creates a space where representatives of different perspectives come together, engage with one another’s contributions and participate in a community of thought. Therefore, attending the whole symposium is obligatory. Due to the nature of the forum audio recording is not permitted.

Presentations are expected to take half an hour. Another 20 minutes is set aside for discussion. There is a 10 min break in between each paper. Please send an abstract of 200 to 300 words, attached in a word-document, to psychoanalysis.politics[at]gmail.com by June 28th 2021. We will respond by, and present a full programme on July 10th 2021.

This is a relatively small symposium where active participation is encouraged and an enjoyable social atmosphere is sought. A participation fee, which includes one shared three course dinner with wine, of € 385 before August 1st 2021 – € 495 between August 1st 2021 and September 4th 2021 – € 585 after September 4th, is to be paid before the symposium.

Your place is only confirmed once we have received your registration including payment is completed. Additional information will be given after your abstract has been accepted or after the programme has been finalized.

We would like to thank the Berlin Psychoanalytical Institute.

Unfortunately, we are unable to offer travel grants or other forms of financial assistance for this event, though we will aim to make a reservation at a nearby hotel with a group discount. You will contact this (or another) hotel individually to book your room. Please contact us if you wish to make a donation towards the conference. We thank all donors in advance!

NB: Please make sure you read the Guide for abstracts thoroughly.

Non-exclusive list of some relevant literature

Adorno, T. W. (1951/1982) “Freudian Theory and the Pattern of Fascist Propaganda” in The Essential Frankfurt School Reader. New York: Continuum.

Adorno, T. W. (1966/1998) “Education After Auschwitz” in Critical Models. Interventions and Catchwords, New York: Columbia University Press.

Anzieu, D. (2001) “Freud’s Group Psychology. Background, Significance and Influence” in E. Spector Person ed. On Freud’s “Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego”. Hillsdale, NJ/ London: The Analytic Press.

Arendt, H. (1951/2004) The Origins of Totalitarianism. New York: Schocken Books.

Arendt, H. (1953/1994) “A Reply to Eric Voegelin” in Essays in Understanding 1930-1954, J. Kohn ed. New York: Schocken Books.

Auestad, L. ed. (2014) Nationalism and the Body Politic: Psychoanalysis and the Rise of Etnocentrism and Xenophobia. London: Karnac/ Routledge.

Auestad, L. (2015) Respect, Plurality, and Prejudice. A Psychoanalytical and Philosophical Enquiry into the Dynamics of Social Exclusion and Discrimination. London: Karnac/ Routledge.

Borossa, J. ed. (2010) Psychoanalysis, Fascism and Fundamentalism. Special issue of Psychoanalysis and History. Edinburgh University Press.

Chigudu, S. (2021) “‘Colonialism had never really ended’: my life in the shadow of Cecil Rhodes” in The Guardian, Jan. 14th https://www.theguardian.com/news/2021/jan/14/rhodes-must-fall-oxford-colonialism-zimbabwe-simukai-chigudu

Davis, A. (1981) Women, Race and Class. New York: Random House.

Erós, F. (2014) “”Budapest, the capital of Hungarians”: rhetoric, images and symbols of the Hungarian extreme right movements” in L. Auestad ed. Nationalism and the Body Politic: Psychoanalysis and the Rise of Ethnocentrism and Xenophobia. London: Karnac/Routledge.

Freud, S. (1912-1913) Totem and Taboo. SE, vol. 13.

Freud, S. (1914) On Narcissism: An Introduction. SE, vol. 14.

Freud, S. (1920) Beyond the Pleasure Principle. SE, vol. 18.

Freud, S. (1921c) Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego. SE, vol. 18.

Freud, S. (1939a [1937-39]) Moses and Monotheism: Three Essays, SE, vol. 23.

Fromm, E. (1997) The Anatomy of Human Destructiveness. Pimlico.

Gandesha, S. ed. (2020) Specters of Fascism. Historical, Theoretical and International Perspectives. London: Pluto Press.

Kaplan, S. (2019) Children in Genocide: Extreme Traumatization and Affect Regulation. Routledge.

Paxton, R. (2004) The Anatomy of Fascism. Vintage Books.

Payne, S. G. (1980) Fascism, Comparison and Definition. University of Wisconsin Press.

Reich, W. (1997) The Mass Psychology of Fascism. Souvenir Press.

Sklar, J. (2019) Dark Times: Psychoanalytic Perspectives on Politics, History and Mourning. UK: Phoenix.

Stanley, J. (2018) How Fascism Works. The Politics of Us and Them. New York: Random House.

Theweleit, K. (1987) Male Fantasies. Vol. I Women, floods, bodies, history. Cambridge, UK/ Malden, MA, USA: Polity Press.